The Salon d’Automne (French: [salɔ̃ dotɔn]; English: Autumn Salon), or Société du Salon d’automne, is an art exhibition held annually in Paris. Since 2011, it is held on the Champs-Élysées, between the Grand Palais and the Petit Palais, in mid-October. The first Salon d’Automne was created in 1903 by Frantz Jourdain, with Hector Guimard, George Desvallières, Eugène Carrière, Félix Vallotton, Édouard Vuillard, Eugène Chigot and Maison Jansen.[1]

Perceived as a reaction against the conservative policies of the official Paris Salon, this massive exhibition almost immediately became the showpiece of developments and innovations in 20th-century painting, drawing, sculpture, engraving, architecture and decorative arts. During the Salon’s early years, established artists such as Pierre-Auguste Renoir threw their support behind the new exhibition and even Auguste Rodin displayed several works. Since its inception, works by artists such as Paul Cézanne, Henri Matisse, Paul Gauguin, Georges Rouault, André Derain, Albert Marquet, Jean Metzinger, Albert Gleizes and Marcel Duchamp have been shown. In addition to the 1903 inaugural exhibition, three other dates remain historically significant for the Salon d’Automne: 1905 bore witness to the birth of Fauvism; 1910 witnessed the launch of Cubism; and 1912 resulted in a xenophobic and anti-modernist quarrel in the National Assembly (France).

History

[edit]

The aim of the salon was to encourage the development of the fine arts, to serve as an outlet for young artists (of all nationalities), and a platform to broaden the dissemination of Impressionism and its extensions to a popular audience.[1] Choosing the autumn season for the exhibition was strategic in several ways: it not only allowed artists to exhibit canvases painted outside (en plein air) during the summer, it stood out from the other two large salons (the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts and Salon des artistes français) which took place in the spring. The Salon d’Automne is distinguished by its multidisciplinary approach, open to paintings, sculptures, photographs (from 1904), drawings, engravings, applied arts, and the clarity of its layout, more or less per school. Foreign artists are particularly well represented. The Salon d’Automne also boasts the presence of a politician and patron of the arts, Olivier Sainsère as a member of the honorary committee.[1]

For Frantz Jourdain, public exhibitions served an important social function by providing a forum for unknown, innovative, emerging (éminents) artists, and for providing a basis for the general public’s understanding of the new art. This was the idea behind Jourdain’s dream of opening a new “Salon des Refusés” in the late 1890s, and realized in the opening the Salon d’Automne in 1903. Providing a venue where unknown artists could be recognized, while ‘wrestling’ the public out of its complacency were, to Jourdain, the greatest contributions to society the critic could make.[2]

The platform of the Salon d’Automne was based on an open admission, welcoming artists in all areas of the arts. Jurors were members of society itself, not members of the Academy, the state, or official art establishments.[2]

Refused exhibition space in the Grand Palais, the first Salon d’Automne was held in the poorly lit, humid basement of the Petit Palais. It was backed financially by Jansen. While Rodin applauded the endeavor, and submitted drawings, he refused to join doubting it would succeed.[2]

Notwithstanding, the first Salon d’Automne, which included works by Matisse, Bonnard and other progressive artists, was unexpectedly successful, and was met with wide critical acclaim. Jourdain, familiar with the multifaceted world of art, predicted accurately the triumph would arouse animosity: from artist who resented the accent on Gauguin and Cézanne (both perceived as retrogressive), from academics who resisted attention given to the decorative arts, and soon, from the Cubists, who suspected the jurors favoring of Fauvism at their expense.[2] Even Paul Signac, president of the Salon des Indépendants, never forgave Jourdain for having founded a rival salon.

What he had not predicted was a retaliation that threatened the future of the new salon. Carolus-Duran (president of the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts) threatened to ban from his Société established artists who might consider exhibiting at the Salon d’Automne. Retaliating in defense of Jourdain, Eugène Carrière (a respected artistic figure) issued a statement that if forced to choose, he would join the Salon d’Automne and resign from the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts. The valuable publicity generated by the press articles on the controversy worked in favor of the Salon d’Automne. Thus, Eugène Carrière saved the burgeoning salon.[2]

Henri Marcel, sympathetic to the Salon d’Automne, became director of the Beaux-Arts, and assured it would take place at the prestigious Grand Palais the following year.[2]

The success of the Salon d’Automne was not, however, due to such controversy. Success was due to the tremendous impact of its exhibitions on both the art world and the general public, extending from 1903 to the outset of the First World War. Each successive exhibition denoted a significant phase in the development of modern art: Beginning with retrospectives of Gauguin, Cézanne and others; the influence such would have on the art that would follow; the Fauves (André Derain, Henri Matisse); followed by the proto-Cubists (Georges Braque, Jean Metzinger, Albert Gleizes, Henri Le Fauconnier, Fernand Léger and Robert Delaunay); the Cubists, the Orphists, and Futurists.[2]

In his defense of artistic liberty, Jourdain attacked not individuals, but institutions, such as the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts, the Société des Artistes Français, and the École des Beaux-Arts (Paris), recognized as the foremost school of art.[2]

In addition to his role as an influential art critic prior to the creation of the Salon d’Automne, Jourdain was a member of the Decorative Arts jury at the Chicago World’s Fair (1893), the Brussels International (1897) and the Paris Exposition Universelle (1900). Jourdain clearly outlined the dangers of following the academic path in his review of the 1889 Exposition, while pointing out the potentials in the art of engineers, aesthetics, the fusion with decorative arts and the need for social reform. He soon became well known as a staunch critic of traditionalism and a fervent proponent of Modernism, yet even for him, the Cubists had gone too far.[2]

1903, the outset

[edit]

The first Salon d’Autumne exhibition opened 31 October 1903 at the Palais des Beaux-Arts de la Ville de Paris (Petit Palais des Champs-Élysées) in Paris.[3] Included in the show were the works of Pierre Bonnard, Coup de vent, Le magasin de nouveautés, Étude de jeune femme (no. 62, 63 and 64); Albert Gleizes, A l’ombre (l’Ile fleurie), Le soir aux environs de Paris (no. 252, 253); Henri Matisse, Dévideuse picarde (intérieur), Tulipes (386, 387), along with paintings by Francis Picabia, Jacques Villon, Édouard Vuillard, Félix Vallotton, Maxime Maufra, Henri Manguin, Armand Guillaumin, Henri Lebasque, Gustave Loiseau, Albert Marquet, Eugene Chigot[4] with an homage to Paul Gauguin who died May 8, 1903.[1]

1904

[edit]

At the 1904 Salon d’Automne, held at the Grand Palais 15 October to 15 November, Jean Metzinger, exhibited three paintings entitled Marine (Le Croisic), Marine (Arromanches), Marine (Houlgate) (no. 907-909); Robert Delaunay, 19 years of age, exhibited his Panneau décoratif (l’été) (no. 352 of the catalogue). Albert Gleizes exhibited two paintings, Vieux moulin à Montons-Villiers (Picardie 1902) and Le matin à Courbevoie (1904), (no. 536, 537). Henri Matisse presented fourteen works (607-620).[5]

Kees van Dongen presented two works, Jacques Villon, three paintings, Francis Picabia three, Othon Friesz four, Albert Marquet seven, Jean Puy five, Georges Rouault eight paintings, Maufra ten, Manguin five, Vallotton three, and Valtat three.[5]

A room at the 1904 Salon d’Automne was dedicated to Paul Cézanne, with thirty-one works, including various portraits, self-portraits, still lifes, flowers, landscapes and bathers (many from the collection of Ambroise Vollard, including photographs taken by the artist, exhibited in the photography section).[5]

Another room presented works of Puvis de Chavannes, with 44 works. And another was dedicated to Odilon Redon with 64 works, including paintings, drawings and lithographs. Auguste Renoir and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec too were represented in separate rooms with 35 and 28 works respectively.[5]

1905, Fauvism

[edit]

After viewing the boldly colored canvases of Henri Matisse, André Derain, Albert Marquet, Maurice de Vlaminck, Kees van Dongen, Charles Camoin, and Jean Puy at the Salon d’Automne of 1905, the critic Louis Vauxcelles disparaged the painters as “fauves” (wild beasts), thus giving their movement the name by which it became known, Fauvism.[6]

Vauxcelles described their work with the phrase “Donatello chez les fauves” (“Donatello among the wild beasts”), contrasting the “orgy of pure tones” with a Renaissance-style sculpture that shared the room with them.[6][7] Henri Rousseau was not a Fauve, but his large jungle scene The Hungry Lion Throws Itself on the Antelope was exhibited near Matisse’s work and may have had an influence on the pejorative used.[8] Vauxcelles’ comment was printed on 17 October 1905 in Gil Blas, a daily newspaper, and passed into popular usage.[7][9] The pictures gained considerable condemnation—”A pot of paint has been flung in the face of the public”, wrote the critic Camille Mauclair (1872–1945)—but also some favorable attention.[7] One of the paintings singled out for attack was Matisse’s Woman with a Hat. This work’s purchase by Gertrude and Leo Stein had a very positive effect on Matisse, who had been demoralized from the bad reception of his work.[7] Matisse’s Neo-Impressionist landscape, Luxe, Calme et Volupté, had already been exhibited at the Salon des Indépendants in the spring of 1905.[10]

Two large retrospectives occupied adjacent rooms at the 1905 Salon d’Automne: one of Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres and the other Édouard Manet.[10]

Despite the reputation for the contrary, the Salon d’Automne in 1905 was rather well received by the press, including critical praise for the Ingres and Manet retrospectives. The artists exhibiting were for the most part known, even the most innovative who a few months before exhibited at the Berthe Weill Gallery. However, a few critics reacted violently, both in the daily press aimed at a wide audience; and in the specialized press, some of whom were active advocates of symbolism, and vehemently detested the rise of the new generation.[11]

1906

[edit]

The exhibition of 1906 was held from 6 October to 15 November. Jean Metzinger exhibited his Fauvist/Divisionist Portrait of M. Robert Delaunay (no. 1191) and Robert Delaunay exhibited his painting L’homme à la tulipe (Portrait of M. Jean Metzinger) (no. 420 of the catalogue).[12] Matisse exhibited his Liseuse, two still lifes (Tapis rouge and à la statuette), flowers and a landscape (no. 1171-1175)[12] Robert Antoine Pinchon showed his Prairies inondées (Saint-Étienne-du-Rouvray, près de Rouen) (no. 1367), now at the Musée de Louviers.[12] Pinchon’s paintings of this period are closely related to the Post-Impressionist and Fauvist styles, with golden yellows, incandescent blues, a thick impasto and larger brushstrokes.[13]

At the same exhibition Paul Cézanne was represented by ten works. He wouldn’t live long enough to see the end of the show. Cézanne died 22 October 1906 (aged 67). His works included Maison dans les arbres (no. 323), Portrait de Femme (no. 235) and Le Chemin tournant (no. 326). Constantin Brâncuși entered three plaster busts: Portrait de M. S. Lupesco, L’Enfant and Orgueil (no. 218 – 220). Raymond Duchamp-Villon exhibited Dans le Silence (bronze) and a plaster bust, Œsope (no. 498 and 499). His brother Jacques Villon exhibited six works. Kees van Dongen showed three works, Montmartre (492), Mademoiselle Léda (493) and Parisienne (494). André Derain exhibited Westminster-Londres (438), Arbres dans un chemin creux (444) and several other works painted at l’Estaque.[12]

Retrospective exhibitions at the 1906 Salon d’Automne included Gustave Courbet, Eugène Carrière (49 works) and Paul Gauguin (227 works).

1907–1909

[edit]

At the exhibition of 1907, held from 1 to 22 October, hung a painting by Georges Braque entitled Rochers rouges (no. 195 of the catalogue). Though this painting remains difficult to identify, it may be La Ciotat (The Cove).[14] Jean Metzinger exhibited two landscapes (no. 1270 and 1271), also difficult to identify.[15]

At this 1907 salon the drawings of Auguste Rodin were featured. There were also retrospectives of the works of Berthe Morisot (174 works) and Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux (149 works), and a Paul Cézanne retrospective exhibition which included 56 works as a tribute to the painter who died in 1906.[16] Apollinaire referred to Matisse as the “fauve of fauves”. Works by both Derain and Matisse are criticized for the ugliness of their models. Braque and Le Fauconnier are considered as Fauves by the critic Michel Puy (brother of Jean Puy).[11] Robert Delaunay showed one work, Bela Czobel showed one work André Lhote showed three, Patrick Henry Bruce three, Jean Crotti one, Fernand Léger five, Duchamp-Villon two, Raoul Dufy three, André Derain exhibited three paintings and Matisse seven works.[16]

For the exhibition of 1908 at the Grand Palais des Champs-Élysées Matisse exhibited 30 works.

At the 1909 exhibition (1 October through 8 November), Henri le Fauconnier exhibited a proto-Cubist portrait of the French writer, novelist and poet Pierre Jean Jouve, drawing the attention of Albert Gleizes who had been working in a similar geometric style.[17] Constantin Brâncuși exhibited alongside Metzinger, Le Fauconnier and Fernand Léger.[11]

1910, the launch of Cubism

[edit]

At the exhibition of 1910, held from 1 October to 8 November at the Grand Palais des Champs-Élysées, Paris, Jean Metzinger introduced an extreme form of what would soon be labeled ‘Cubism’, not just to the general public for the first time, but to other artists that had no contact with Picasso or Braque. Though others were already working in a proto-Cubist vein with complex Cézannian geometries and unconventional perspectives, Metzinger’s Nu à la cheminée (Nude) represented a radical departure further still.[18]

I have in front of me a small cutting from an evening newspaper, The Press, on the subject of the 1910 Salon d’Automne. It gives a good idea of the situation in which the new pictorial tendency, still barely perceptible, found itself: The geometrical fallacies of Messrs. Metzinger, Le Fauconnier, and Gleizes. No sign of any compromise there. Braque and Picasso only showed in Kahnweiler’s gallery and we were unaware of them. Robert Delaunay, Metzinger and Le Fauconnier had been noticed at the Salon des Indépendants of that same year, 1910, without a label being fixed on them. Consequently, although much effort has been put into proving the opposite, the word Cubism was not at that time current. (Albert Gleizes, 1925)[19]

In a review of the Salon, the poet Roger Allard (1885-1961) announces the appearance of a new school of French painters concentrating their attention on form rather than on color. A group forms that includes Gleizes, Metzinger, Delaunay (a friend and associate of Metzinger), and Fernand Léger. They meet regularly at Henri le Fauconnier’s studio near the Bld de Montparnasse, where he is working on his ambitious allegorical painting entitled L’Abondance. “In this painting” writes Brooke, “the simplification of the representational form gives way to a new complexity in which foreground and background are united and the subject of the painting obscured by a network of interlocking geometrical elements”.[20]

This exhibition preceded the 1911 Salon des Indépendants which officially introduced “Cubism” to the public as an organized group movement. Metzinger had been close to Picasso and Braque, working at this time along similar lines.[15]

Metzinger, Henri Le Fauconnier and Fernand Léger exhibited coincidentally in Room VIII. This was the moment in which the Montparnasse group quickly grew to include Roger de La Fresnaye, Alexander Archipenko and Joseph Csaky. The three Duchamp brothers, Marcel Duchamp, Jacques Villon and Raymond Duchamp-Villon, and another artist known as Picabia took part in the exhibition. Following this salon Metzinger wrote the article Notes sur la peinture,[21] in which he compares the similarities in the works Picasso, Braque, Delaunay, Gleizes and Le Fauconnier. In doing so he enunciated for the first time what would become known as the characteristics of Cubism: notably the notions of simultaneity, mobile perspective. In this seminal text Metzinger stressed the distance between their works and traditional perspective. These artists, he wrote, granted themselves ‘the liberty of moving around objects’, and combining many different views in one image, each recording varying experiences over the course of time.[17][22]

Once launched at the 1910 Salon d’Automne, the new movement would rapidly spread throughout Paris.

Convinced that exposure to the work of German designers would prompt healthy competition in the decorative arts, Frantz Jourdain invited artists, architects, designers, and industrialists from the Munich-based Deutscher Werkbund to exhibit at the 1910 salon. “Our art menaced by Bavarian decorators” read the headline of the journal Le Radical (12 May 1910). This scandal, in addition to the non-French status of the authors in a time of growing nationalism, aroused the old polemic of exhibiting low-cost production objects, mass-produced items, simply designed furniture and interior decoration, in the context of a salon dedicated to art. Industrial art had never before been so controversial. The exhibition was reviewed in all the major journals. Louis Vauxcelles added to the crisis in a Gil Blas article.[2]

The exhibition was an enormous success in that it served to catalyze anew designers, decorators, artists and architects in France, who prior to the 1910 Salon d’Automne had been lagging behind in the design sector. It also catalyzed public opinion, formerly interested solely in paintings. The fact that the viewers saw first hand, and many for the first time, what had been done abroad, opened up a potential of what could be done in the field of decorative arts at home. Jourdain had successfully staged the German show to provoke French designers into improving the quality of their own work. The effects would be felt in Paris, first with the 1912 exhibition of French decorative arts at the Pavillon de Marsan, then again at the Salon d’Automne of 1912, with La Maison Cubiste,[2][23] the collaborative effort of the designer André Mare, Raymond Duchamp-Villon and other artists associated with the Section d’Or.

Henri Matisse exhibited La Danse at the Salon d’Automne of 1910.[24]

1911, the rise of Cubism

[edit]

In Room 7 and 8 of the 1911 Salon d’Automne, held 1 October through November 8, at the Grand Palais in Paris, hung works by Metzinger (Le goûter (Tea Time)), Henri Le Fauconnier, Fernand Léger, Albert Gleizes, Roger de La Fresnaye, André Lhote, Jacques Villon, Marcel Duchamp, František Kupka, Alexander Archipenko, Joseph Csaky and Francis Picabia. The result was a public scandal which brought Cubism to the attention of the general public for the second time. The first was the organized group showing by Cubists in Salle 41 of the 1911 Salon des Indépendants. In room 41 hung the work of Gleizes, Metzinger, Léger, Delaunay, Le Fauconnier and Archipenko. Articles in the press could be found in Gil Blas, Comoedia, Excelsior, Action, L’Œuvre, Cri de Paris. Apollinaire wrote a long review in the April 20, 1911, issue of L’Intransigeant.[17] Thus Cubism spread into the literary world of writers, poets, critics, and art historians.[25]

Apollinaire took Picasso to the opening of the Salon d’Automne in 1911 to see the cubist works in Room 7 and 8.[26]

Albert Gleizes writes of the Salon d’Automne of 1911: “With the Salon d’Automne of that same year, 1911, the fury broke out again, just as violent as it had been at the Indépendants.” He writes: “The painters were the first to be surprised by the storms they had let loose without intending to, merely because they had hung on the wooden bars that run along the walls of the Cours-la-Reine, certain paintings that had been made with great care, with passionate conviction, but also in a state of great anxiety.”[19]

It was from that moment on that the word Cubism began to be widely used. […]

Never had the critics been so violent as they were at that time. From which it became clear that these paintings – and I specify the names of the painters who were, alone, the reluctant causes of all this frenzy: Jean Metzinger, Le Fauconnier, Fernand Léger, Robert Delaunay and myself – appeared as a threat to an order that everyone thought had been established forever.

In nearly all the papers, all composure was lost. The critics would begin by saying: there is no need to devote much space to the Cubists, who are utterly without importance and then they furiously gave them seven columns out of the ten that were taken up, at that time, by the Salon. (Gleizes, 1925)[19]

Reviewing the Salon d’Automne of 1911, Huntly Carter in The New Age writes that “art is not an accessory to life; it is life itself carried to the greatest heights of personal expression.” Carter continues:

It was at the Salon d’Automne, amid the Rhythmists, I found the desired sensation. The exuberant eagerness and vitality of their region, consisting of two rooms remotely situated, was a complete contrast to the morgue I was compelled to pass through in order to reach it. Though marked by extremes, it was clearly the starting point of a new movement in painting, perhaps the most remarkable in modern times, It revealed not only that artists are beginning to recognise the unity of art and life, but that some of them have discovered life is based on rhythmic vitality, and underlying all things is the perfect rhythm that continues and unites them. Consciously, or unconsciously, many are seeking for the perfect rhythm, and in so doing are attaining a liberty or wideness of expression unattained through several centuries of painting. (Huntly Carter, 1911)[27][28]

1912, political ramifications

[edit]

The Salon d’Automne of 1912 was held in Paris at the Grand Palais from 1 October to 8 November. The Cubists (a group of artists now recognized as such) were regrouped into the same room, XI.

The 1912 polemic leveled against both the French and non-French avant-garde artists originated in Salle XI of the Salon d’Automne where the Cubists, among whom were several non-French citizens, exhibited their works. The resistance to both foreigners and avant-garde art was part of a more profound crisis: that of defining modern French art in the wake of Impressionism centered in Paris. Placed into question was the modern ideology elaborated upon since the late 19th century. What had begun as a question of aesthetics quickly turned political during the Cubist exhibition, and as in the 1905 Salon d’Automne, the critic Louis Vauxcelles (in Les Arts…, 1912) was most implicated in the deliberations. It was also Vauxcelles who, on the occasion of the 1910 Salon des Indépendants, wrote disparagingly of ‘pallid cubes’ with reference to the paintings of Metzinger, Gleizes, Le Fauconnier, Léger and Delaunay.[29] On 3 December 1912 the polemic reached the Chambre des députés (and was debated at the Assemblée Nationale in Paris).[30][31]

In his 1921 essay on the Salon d’Automne, published in Les Echos (p. 23), founder Frantz Jourdain denouncing aesthetic snobbery, writes that the saber-rattling revolutionaries dubbed the Cubists, Futurists and Dadaists were actually crusty reactionaries who scorned modern progress and revealed contempt for democracy, science, industry and commerce.[2]

For Jourdain, the ‘modern spirit’ signified more than a preference for Cézanne over Gérome. Needed was a clear understanding of one’s epoch, its needs, its beauty, its ambience, its essence.[2]

1 October through 8 November 1912, in excess of 1,770 works were displayed at the 10th Salon d’Automne. Paul Gallimard organized the exhibition of 52 books. The poster for the 1912 show was made by Pierre Bonnard. Sessions of chamber music took place every Friday. Morning literary sessions were held every Wednesday. The cost of the catalogue was 1 French Franc. The decoration of the Salon d’Automne had been entrusted to the department store Printemps.[32]

Jourdain again came under vicious attack in 1912—as the French nation drew closer to war in a conservative and fiercely nationalistic political climate—now by the dean of the Conseil Municipal and member of the city’s Commission des Beaux-Arts, Jean Pierre Philippe Lampué. Lampué argued, unsuccessfully, that the Salon d’Automne be refused use of the Grand Palais on the grounds that the organizers were unpatriotic and were undermining—with their foreign “Cubo-Futurist” exhibitions—the artistic heritage of France. He did however manage to raise public opinion against the Salon d’Automne, the Cubists and Jourdain specifically. The huge scandal prompted the critic Roger Allard to defend Jourdain and the Cubists in the journal La Côte, pointing out that it wasn’t the first time the Salon d’Automne—as a venue to promote modern art—came under attack by city officials, the Institute, and members of the Conseil. And it would not be the last either.[2]

The Salon d’Automne from its very inception was one of the most significant avant-garde venues, exhibiting not just painting, drawing and sculpture, but industrial design, urbanism, photography, new developments in music and cinema.[2]

According to Albert Gleizes, Frantz Jourdain (in second place after Vauxcelles) was the sworn enemy of the Cubists, so much so that in his later writing on the Salon d’Automne Jourdain makes no mention of the 1911 or 1912 exhibitions, yet the publicity generated by the Cubist polemic brought a supplement of 50,000 French Francs, due to influx of visitors that came to see Les monstres.[33]

To appease the French, Jourdain invited the pontiffs des Artistes Français, writes Gleizes, to an “exposition de portraits” specially organized at the salon.[33] 220 portraits painted during the 19th century were displayed.[32] A reversal of the situation arose, unfortunately for Jourdain, when the guests had to pass through the Cubist room in order to access the portraits. Speculation has it that the itinerary had been judiciously chosen by the hanging committee, since everyone at the Automne seems to have understood.[33]

The Cubist room was packed full with spectators, and others waited in line to get in, explains Gleizes, while no one paid any attention to the portrait room. The consequences, were ‘disastrous’ for Jourdain, who, as president of the salon, was ultimately held responsible for the debacle.[33]

Jules-Louis Breton, the French socialist militant politician (nephew of the academic painter Jules Breton), launched a poignant attack against the Cubists exhibiting at the Salon d’Automne. Breton, with the support of Charles Benoist, accused the French government of sponsoring the excesses of the Cubists by virtue of providing an exhibition space at the Grand Palais. Against the attacks of his colleagues, Marcel Sembat, the French socialist politician, defended the principles of freedom of expression, while refusing the idea of a state-sponsored art. Sembat, closely linked to the arts, with friends including Marquet, Signac, Redon and Matisse (about whom he would write a book[34]). His wife, Georgette Agutte, an artist associated with the Fauves, had exhibited from 1904 at the Salon des Indépendants and participated in the founding of the Salon d’Automne (her art collection included works by Derain, Matisse, Marquet, Rouault, Vlaminck, Van Dongen, and Signac). Charles Beauquier, the politician and self-proclaimed free-thinker (“libre-penseur”) sided with Breton and Benoist: “We do not encourage garbage! There is garbage in the arts and elsewhere”.[35][36][37]

Ultimately, Marcel Sembat won the debate on several fronts: the Salon d’Automne remained at the Grand Palais des Champs Elysées for years to come; the press coverage following the Assemblée nationale’s discussions was as intense as it was widespread, publicizing Cubism still further; the reverberations caused by the Cubist scandal echoed across Europe, and elsewhere, extending far beyond what would have been predicted without such publicity. Marcel Sembat would soon become Minister of Public Works; from 1914 to 1916, under Prime Ministers René Viviani and Aristide Briand.[38][39]

Works exhibited at the 1912 Salon d’Automne

[edit]

- Jean Metzinger entered four works: Dancer in a café, titled Danseuse (Albright-Knox Art Gallery), La Plume Jaune (The Yellow Feather), Paysage (Landscape), and Femme à l’Éventail (Woman with a Fan) (Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York), hung in the decorative arts section inside La Maison Cubiste (the Cubist House).

- Francis Picabia, 1912, La Source (The Spring) (Museum of Modern Art, New York)

- Fernand Léger exhibited La Femme en Bleu (Woman in Blue), 1912 (Kunstmuseum, Basel) and Le passage à niveau (The Level Crossing), 1912 (Fondation Beyeler, Riehen, Switzerland)

- Roger de La Fresnaye, Les Baigneuses (The bathers) 1912 (The National Gallery, Washington) and Les joueurs de cartes (Card Players)

- Henri Le Fauconnier, The Huntsman (Haags Gemeentemuseum, The Hague, Netherlands) and Les Montagnards attaqués par des ours (Mountaineers Attacked by Bears) 1912 (Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design).

- Albert Gleizes, L’Homme au Balcon, Man on a Balcony (Portrait of Dr. Théo Morinaud), 1912 (Philadelphia Museum of Art), also exhibited at the Armory show, New York, Chicago, Boston, 1913.

- André Lhote, Le jugement de Pâris, 1912 (Private collection)

- František Kupka, Amorpha, Fugue à deux couleurs (Fugue in Two Colors), 1912 (Narodni Galerie, Prague), and Amorpha Chromatique Chaude.

- Alexander Archipenko, Family Life, 1912, sculpture (destroyed)

- Amedeo Modigliani, exhibited four sculptures of elongated and highly stylized heads

- Joseph Csaky exhibited the sculptures Groupe de femmes, 1911-12 (location unknown), Portrait de M.S.H., no. 91 (location unknown), and Danseuse (Femme à l’éventail, Femme à la cruche), no. 405 (location unknown)

La Maison Cubiste (Cubist House)

[edit]

Main article: La Maison Cubiste

This Salon d’Automne also featured La Maison Cubiste. Raymond Duchamp-Villon designed façade of a 10 meter by 3 meter house, which included a hall, a living room and a bedroom. This installation was placed in the Art Décoratif section of the Salon d’Automne. The major contributors were André Mare, a decorative designer, Roger de La Fresnaye, Jacques Villon and Marie Laurencin. In the house were hung cubist paintings by Marcel Duchamp, Albert Gleizes, Fernand Léger, Roger de La Fresnaye, and Jean Metzinger (Woman with a Fan, 1912).

While the geometric decoration of the plaster façade and the paintings were inspired by cubism, the furnishings, carpets, cushions, and wallpapers by André Mare were the beginning of a distinct new style, Art Deco. They were extremely colorful, and consisted of floral designs, particularly stylized roses, in geometric patterns. Thsee themes were to reappear in decoration after the First War through the firm founded by Mare.

Metzinger and Gleizes in Du “Cubisme”, written during the assemblage of the “Maison Cubiste”, wrote about the autonomous nature of art, stressing the point that decorative considerations should not govern the spirit of art. Decorative work, to them, was the “antithesis of the picture”. “The true picture” wrote Metzinger and Gleizes, “bears its raison d’être within itself. It can be moved from a church to a drawing-room, from a museum to a study. Essentially independent, necessarily complete, it need not immediately satisfy the mind: on the contrary, it should lead it, little by little, towards the fictitious depths in which the coordinative light resides. It does not harmonize with this or that ensemble; it harmonizes with things in general, with the universe: it is an organism…”.[40] “Mare’s ensembles were accepted as frames for Cubist works because they allowed paintings and sculptures their independence”, wrote Christopher Green, “creating a play of contrasts, hence the involvement not only of Gleizes and Metzinger themselves, but of Marie Laurencin, the Duchamp brothers (Raymond Duchamp-Villon designed the façade) and Mare’s old friends Léger and Roger La Fresnaye”.[41] La Maison Cubiste was a fully furnished house, with a staircase, wrought iron banisters, a living room—the Salon Bourgeois, where paintings by Marcel Duchamp, Metzinger (Woman with a Fan), Gleizes, Laurencin and Léger were hung—and a bedroom. It was an example of L’art décoratif, a home within which Cubist art could be displayed in the comfort and style of modern, bourgeois life. Spectators at the Salon d’Automne passed through the full-scale 10-by-3-meter plaster model of the ground floor of the façade, designed by Duchamp-Villon.[42] This architectural installation was subsequently exhibited at the 1913 Armory Show, New York, Chicago and Boston,[43] listed in the catalogue of the New York exhibit as Raymond Duchamp-Villon, number 609, and entitled “Façade architectural, plaster” (Façade architecturale).[44][45]

For the occasion, an article entitled Au Salon d’Automne “Les Indépendants” was published in the French newspaper Excelsior, 2 Octobre 1912.[46] Excelsior was the first publication to privilege photographic illustrations in the treatment of news media; shooting photographs and publishing images in order to tell news stories. As such L’Excelsior was a pioneer of photojournalism.

1913–1914

[edit]

By 1913 the predominant tendency in modern art visible at the Salon d’Automne consisted of Cubism with a clear tendency towards abstraction. The trend to use brighter colors that had already begun in 1911 continued through 1912 and 1913. This exhibition, held from 15 November to 8 January 1914, was dominated by de La Fresnaye, Gleizes and Picabia. Works by Delaunay, Duchamp and Léger were not exhibited.[17]

The preface of the catalog was written by the French Socialist politician Marcel Sembat who a year earlier—against the outcry of Jules-Louis Breton regarding the use of public funds to provide the venue (at the Salon d’Automne) to exhibit ‘barbaric’ art—had defended the Cubists, and freedom of artistic expression in general, in the National Assembly of France.[20][30][47][48]

“I do not in the least wish… to offer a defense of the principles of the cubist movement! In whose name would I present such a defense? I am not a painter… What I do defend is the principle of the freedom of artistic experimentation… My dear friend, when a picture seems bad to you, you have the incontestable right not to look at it, to go and look at others. But one doesn’t call the police!” (Marcel Sembat)[47]

This exhibition too made its flashing appearance in the news, when a nude by Kees van Dongen entitled The Spanish Shawl (Woman with Pigeons or The Beggar of Love) was ordered by the police to be removed from the Salon d’Automne. The same would happen in Rotterdam at the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen in 1949. The painting is now on display at the Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris.[17][49]

After 1918

[edit]

During World War I (1914 through 1918) no Salon d’Automne exhibition was held. It wasn’t until the autumn of 1919 that the Salon d’Automne once again took place, from 1 November to 10 December, at the Grand Palais in Paris. Special attention, that is, a retrospective, was given to Raymond Duchamp-Villon who died on 9 October 1918. On display were 19 works by the French sculptor dated between 1906 and 1918.[17]

After the war, the Salon d’Automne was dominated by the works of the Montparnasse painters such as Marc Chagall, Amedeo Modigliani, Georges Braque and Georges Gimel. The Polish expressionist painter Henryk Gotlib and Scottish expressionist painter David Atherton-Smith also exhibited. Constantin Brâncuși, Aristide Maillol, Charles Despiau, René Iché, Ossip Zadkine, and Mateo Hernandez emerged as new forces in sculpture.

In addition to painting and sculpture, the Salon included works in the decorative arts such as the glassworks of René Lalique, Julia Bathory as well as architectural designs by Le Corbusier. Still an exhibition of world importance, the Salon d’Automne is now into its 2nd century.

The Avant-Garde in Paris

[edit]

In an exhibition entitled Picasso and the Avant-Garde in Paris (February 24, 2010 – May 2, 2010),[50] the Philadelphia Museum of Art showcased a partial reconstruction of the 1912 Salon d’Automne. Many of the works exhibited, however, had not been on display at the 1912 salon, while others exhibited in 1912 were conspicuously absent. The exhibition served to highlight the importance of the Salon Cubism—usually pitted against Gallery Cubism as two opposing camps—in developments and innovations of 20th-century painting and sculpture.

1922, Braque

[edit]

Fourteen years after the rejection of Georges Braque‘s L’Estaque paintings by the jury of the Salon d’Automne of 1908 (composed of Matisse, Rouault, Marquet, and Charles-François-Prosper Guérin), Braque was given the accolade of the Salle d’Honneur in 1922, without incident.[51]

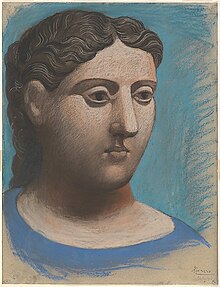

1944, Picasso at the Salon d’Automne

[edit]

In a dramatic case of situational irony, a room at the Salon d’Automne was dedicated to Picasso in 1944. During the crucial years of Cubism, between 1909 and 1914, the dealer Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler forbade Braque and Picasso from exhibiting at both the Salon d’Automne and the Salon des Indépendants. He thought the salons were places of humor and ribaldry, of jokes, laughter and ridicule. Fearing that Cubism would not be taken seriously in such public exhibitions where thousands of spectators would assemble to see new creations, he signed exclusivity contracts with his artists, ensuring that their works could only be shown (and sold) in the privacy of his own gallery.[52]

After the Liberation of Paris, the first post-World War II Salon d’Automne was to be held in the fall of 1944 in the newly freed capital. Picasso was given a room of his own that he filled with examples of his wartime production. It was a triumphant return for Picasso who had remained aloof from the art scene during the war. The exhibition however, was “marred by disturbances that have remained unattributed” according to Michèle C. Cone (New York-based critic and historian, author of French Modernisms: Perspectives on Art before, during and after Vichy, Cambridge 2001). On Nov. 16, 1944, Matisse wrote a letter to Camoin: “Have you seen the Picasso room? It is much talked about. There were demonstrations in the street against it. What success! If there is applause, whistle.” One can guess who the demonstrators might have been, writes Cone, “cronies of the Fauves, still ranting against the Judeo-Marxist decadent Picasso”.[53][54]